What you need to know to create a solar array on the water.

A new trend in photovoltaic arrays sweeping the world and slowly finding a home in select regions of the United States is “floatovoltaics”—a solar array that floats on water.

Heavy power users near bodies of water, like water treatment facilities, could save hundreds of thousands of dollars per year by using electricity generated by an adjacent floating solar installation. Since lease payments for underutilized bodies of water are likely to be lower than land lease payments, a floating installation could be even more competitive compared to other energy sources. Additionally, owners of bodies of water could benefit from modest revenue streams by leasing their water surface to solar developers or to utilities.

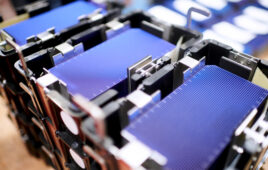

A floating PV array. Photo courtesy of Ciel et Terre.

Currently, floatovoltaic projects are popular in countries like Singapore and Japan, which have ample water resources on which to float arrays, but the market is growing worldwide.

There are a handful of installations in the United States now, but the clear leader in the market is Japan. As an island (and a smallish one at that), there’s not a lot of room to build land-based arrays. Instead, following the United States’ lead, the Japanese started floating solar arrays near cities.

The beauty of water-based solar arrays is they can exist in almost any water body—ponds, lakes, canals and reservoirs. As the world population becomes ever larger and land becomes scarcer, floatovoltaics are turning into a viable option.That’s why it takes the right equipment—from panels to wiring to platform to aftercare—to ensure the array produces as intended. Here are three things you must consider before installing a floatovoltaic system.

Keep components above water

It might be counterintuitive to think of an electricity-generating plant floating in the middle of a river or lake. After all, if you stand in a puddle and touch an open circuit, you won’t live long.

That’s why special racking is required for floating arrays. It must have the strength to hold panels in place but be flexible enough to deal with waves that can reach up to 3.28 ft, all the while keeping the array safe from harm. The current leader in floatovoltaic racking is a French company called Ciel et Terre (“Heaven and Earth” in English), and it has provided the racking for most current floating arrays worldwide.

Floating solar panels must stay at least 3 ft above water and should not be installed on water with high salinity. Even in water with a low salt content (no more than 15 practical salinity units (PSU)), water can degrade components, leading to lower production.

Keeping wiring and cables from being splashed and corroded is essential. Make sure they are isolated, insulated and at least 1.6 ft above the water.

Pick the perfect panels

When it comes to water-bound arrays, not all panels are created equal. If they are not designed specifically to be waterproof, you could find yourself in trouble.

All modules installed in floating arrays should have the proper ingress protection (IP) rating for the connectors and junction box. The IP rating helps classify products resistant to water intrusion beyond the vague statement of being “waterproof.” Most solar modules have an IP rating that can protect them from “splashing water” (IP64) all the way to submersion in 3.28 ft of water for 30 minutes (IP67). REC solar modules are IP67 rated. The National Electrical Manufacturers Association defines NEMA enclosure types in NEMA standard number 250.

The key component of panels in these environments is the encapsulant. Many panel manufacturers don’t pay close attention to their encapsulants because they are not planning to do water-based installations. But project managers for marine-based arrays must investigate which encapsulant the panels have and what its IP rating is. Nothing can destroy reputations faster than arrays that degrade before investors recoup their investments.

Keep the birds at bay

Birds only need two things to survive: water and food sources. While floating arrays don’t have the latter, they are by definition surrounded by the former—which means you will often find flocks of waterfowl nesting nearby. And if there is enough guano on the array, it can prevent electricity production.

The easiest way to prevent soiling is to keep birds off the array in the first place, which can take the form of bird spikes, netting and strips that provide a little electric shock (not enough to harm them, just enough to make it uncomfortable). On floating arrays, most owners use bird spikes or netting, although netting is better because the spikes have the potential to throw shadows on the array and degrade power output.

Of course, if the birds do soil the array, the problem becomes an operations and maintenance issue. How do you get people or machines out to the array to keep the panels clean? There is no best practice at the moment, but REC is in the process of putting together a manual to standardize the process.

In the end, if you pay attention to these three guidelines, you can install a successful “floatovoltaic” project. It’s a brave new frontier for the solar industry in the United States, but it is growing. It’s something the best installers will know how to do if they want to grow.

This article was written by George McClellan, technical sales manager for REC Group.

If you look carefully in my Facebook picture, you will see water in the background. Having designed just about everything that is floatable for some kind of use, it seems that the “floatovoltaic” concept of REC covers most of the issues.

Stainless steel leader wire properly oriented and supported (tensioned with wind-induced harmonic suppression) at potential perching points will largely solve the bird problem.

I have always wondered how much movement (by rate and gross amount) in altering the incident angle can be tolerated for a 1-sun system feeding inverters, as opposed to batteries, such as is the case with PV on vehicles, boats, etc. Wave energy abatement around an array field can be a big deal as fetch lengthens and wind builds. Arrays of articulating floats can be sized for unit and array mass and dimensions to minimize movement for a known wave regime. Thin shell (so-called ferro-cement) “concrete” laminates would be well suited as flotation, especially where icing may occur.

As a solar power entrepreneur I am committed to a solar-powered world (www.esolartech.com ). But I vehemently disagree that every inch of open space is crying out to be covered in solar arrays. Open bodies of naturally occuring water need sunlight directly coming through for the health of the entire eco-system the core of which is photosynthesis. Putting a layer of photovoltaics on what appears a relatively significant area of this pond is no different than paving over the same dimensions with a cement layer. It seems irresponsible no differently than Fossil Fuel companies compromise eco-systems, human populations and the atmosphere in the name of profit. The promise of solar is not to replace conventional forms of environmental destruction in the name of Energy with one that is more “high-tech.”

The Earth is mostly water so there certainly must be applications for water-born PV. This seems not to be one.